TRANSCRIPT

The colorblind are disabled.

This is not ragebait, this is what I believe, and I imagine if this video takes off, it’s going to be because the vast majority of you vehemently disagree with that statement… and with the help of my sister and a friend, I’m going to try and change your mind.

Merriam Websters defines…

Dalton: “oh come on, you’re better than that”

Oxford English Dictionary defines…

Dalton: “Dig deeper sonny!”

Let’s go outside…

This is how I walk… I know right, in the last 3 years, you’ve never seen me stand before, have you. Actually, this is just temporary as a result of a knee surgery. As such, it doesn’t even qualify me as disabled in most countries since it is not a LONG-TERM condition, but it certainly has been an interesting foray into the life of a visibly disabled person, with strangers touching my things or myself without stopping to consider whether I need or want their help.

Spectrum

In the broad sense, disability is some kind of physical or mental, long-term impairment to conducting your day-day activities.

Disability is not black and white, it lies along a spectrum, and yes, I did just double color vision pun you. There are different severities of disability and I’m not gonna resort to some disability tier list, but while you may consider Oscar Pistorius and Stephen Hawking as both disabled, one was clearly much more disabled than the other. So where do we draw that line between able and disabled, and which side are the colorblind on?

Paraplegic

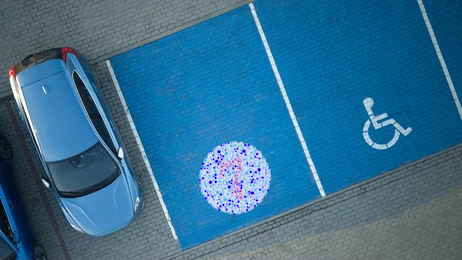

If you are anything like me 10 years ago, when I heard disabled, this image is the first thing that pops into my head. This isn’t necessarily because paraplegia is the most common or because it’s the most “severe”, but rather because it is hyper-visible and very relatable.

I don’t think I have to argue the visibility point. After all, it’s impossible to miss a woman in a wheelchair rolling up the street whereas you would never notice the deaf kid on his bike.

By relatability, I mean that an able person can accurately imagine or even simulate that disability in themselves. The impairments stemming from paraplegia can be understood by most people after just a little exposure to paraplegics. Likewise, paraplegics can usually imagine life as able-bodied, especially since most paraplegics started life as able-bodied, so it’s easier for them to explain how the condition affects them. When a paraplegic encounters a hurdle, either figurative or literal, they immediately know that it is a hurdle.

A very unrelatable disability would be OCD, which can’t be simulated and the fact that many people have a fundamental misunderstanding of it also shows that it’s not well understood or accurately imagined. Hence why people who think OCD is simply being a neat freak wouldn’t consider OCD a disability when it very much is.

Let’s compare this to colorblindness. Not only is it an entirely invisible condition, but it’s also quite unrelatable. Color normals cannot easily understand what colorblindness looks or feels like or how it might affect them. If I ask 100 people on the street to describe color blindness to me, I doubt more than 5 would even get close.

Likewise the colorblind cannot at all imagine what it would be like to have normal color vision, partly because we were born colorblind. So it’s generally hard for us to explain colorblindness in a way that makes sense to a color normal.

Also, when the colorblind encounter a hurdle, we usually have no idea that we are perceiving something differently than everyone else, so it’s often hard to know whether a task is difficult because we’re colorblind, or if it’s simply difficult for everyone.

Trivial

Because of this lack of relatability, it often sounds like the impairments we experience are quite trivial. Ask a colorblind person open-ended questions like “what’s hard about being colorblind” and you hear:

- Cooking meat is hard?

- Buying ripe bananas is hard?

- Matching clothes is hard?

- Painting is hard?

- Boardgames are hard?

Hell, even if you ask leading color vision researchers, you get answers like:

“having difficulty navigating the highly color-coded World Wide Web on the computer Internet”

[Neitz, 2000]

All of these sound super banal, which ends up making it seem that colorblindness is trivial, and it COULD be mostly trivial, except for one other problem: discrimination in the job market.

Burping

Let me tell you a story. I had an uncle with a strange condition, he had developed uncontrollable… burping, and he considered it a disability. Had he lived in the US, he would not be treated as disabled under the ADA as the burping did not affect his day-to-day activities, besides making him functionally celibate.

Luckily for him, he lived in Canada, where he was able to demonstrate that the burping grossly affected his career as a retail salesman. Ridiculous, but realistic, and you can probably relate to how uncontrollable burping would definitely hold you back in MOST professions. After his company demonstrated that there were no reasonable accommodations to give him and after he showed that he was too old to be retrained in a role where his burping would be acceptable, he collected disability benefits until he was able to “retire” from his disability and ironically spend the rest of his days posting anti-immigrant memes on facebook, because unlike him, THEY were all “leeches on society”.

Discrimination

All this to say, a condition that affects your livelihood more than your life… can STILL be a big disadvantage. 30% of the colorblind have had their career directly interrupted by their color blindness. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think that the colorblind should be collecting disability benefits, but the color vision requirements of most of these careers can be neutralized by either policy makers better understanding color vision science, or by trivial changes to the procedures or equipment used by the color blind employee.

I don’t want you to consider colorblindness a disability so that I can get a better parking space or something. What I really want is simply common sense accommodations… ways for organizations to be accessible to the colorblind, and especially their colorblind employees. These accommodations should be promoted, and in some cases enforced to stop organizations from excluding the colorblind with blithe disregard, to stop them… discriminating.

Models

Here’s the crux of the problem… you and the majority of policy makers view disability under the medical model of disability. In this model, a disability is something that should ideally be fixed through medical intervention, so the person can better fit into society. That if something prevents a woman from climbing the stairs, then we need to fix the woman so she can climb stairs.

The counterideology is of course, that we fix the stairs to be accessible to the woman, for example, by adding a ramp. This is the social model of disability, that the disability need not be pathologized, and that society should focus on accessibility and accommodation instead of treatment.

Neither model is right or wrong, but they are both useful lenses for looking at certain disabilities or aspects thereof.

For example, autists and the deaf generally do not consider themselves to have a disease and instead the condition is part of their identity and they usually reject the medical model, but they do consider themselves disabled under the social model, as they still expect accommodations like sign language interpreters in public meetings.

The social model is great for viewing those disabilities, but is lacking for others, namely for acquired disabilities. If you have been fully sighted your whole life, but develop cataracts in your 60’s, then this is very much a disability that is and should be viewed in the medical model, just like depression, parkinsons, alzheimers, things that those with the disability will tend to view as a DISEASE instead of their IDENTITY.

So YOUR rejection of color blindness as a disability is likely coming from a mindset fixed in the medical model of disability and the majority of the colorblind would agree that the actual biomedical, functional impairment to our color vision is slight, especially in our day-to-day activities.

Most of us believe it is problematic to apply the medical model to colorblindness and I personally even believe – though this may be a minority view – that it is not something that should be cured, even if it were possible. My color vision has become a significant part of my identity and at this point, if given the choice, shockingly, I’d keep it.

Instead, we prefer to view colorblindness through the social model of disability, which expects that society improve accessibility by providing reasonable accommodations. Hell, I’d even go so far to say that a condition need not even qualify as a disability at all to deserve this kind of support, and for that, I want to talk to some special guests who have no idea what this video is about.

Interviews

Curran: I want to ask you a little question: could you tell the viewers a little bit more about your disability

Madi: My disability… you mean my disability of being left-handed?

Meghan: Oh being left-handed? That’s not a disability

Madi: um my disability of being left-handed… uh… it really impacts the things I do daily! I mean not really

Chromaphobe: oh no am I going to try and convince you that left-handedness is a disability? Let’s see!

Curran: How would you say that it affects you in your life?

Madi: um… well I mean the biggest thing I could say right now are scissors, and every time I find a new pair of scissors I have to learn how to use them… um… what else?

Curran: It’s kind of a crap question isn’t it? Kind of, like, struggling to come up with any answer just kind of makes it seem trivial? The fact that the first thing you mention are scissors… most people would be, like, “well if I had a little bit of trouble with scissors I feel like that wouldn’t affect my life greatly!” [Laughter]

Madi: no… I mean, how often do you pick up a pair of scissors?

Meghan: um, there’s definitely times when I’m, you know, doing work or something and trying to get some screws into a machine and it’s all built to be accessed by a right-handed person, so everything’s just like that little tiny bit more awkward.

Madi: …because it’s just a part of you or you know something you’ve had to deal with for so long you don’t really think of it twice or you, you know, dismiss your own struggle, or you dismiss your own effort that you put into overcoming such a struggle. Did you know that steak knives are handed?

Curran: okay no I did not know that.

Madi: yeah, because the serration is on one side of the knife so if you hold it in your right hand it’ll cut, you know, maybe on this angle… but once you pick it up with your left hand it’ll still cut on that angle and then you slide up so you have to just change the angle of your uh of your wrist and then you can make it happen. But I’ve pointed out in a group setting like, “ah this steak Knife it’s not left-handed,” and they’re like, “what there’s no such thing as a left-handed steak knife,” and I’m like, “yes let me prove it to you,” and I have to show it and then it becomes like a bit of a parlor trick or a joke… but uh yeah I’ve been I’ve been discriminated against

Meghan: The only thing I can really remember is in University some right-handed person took one of the like five left-handed desks in the lecture hall and he would not get up and move so that I could have a left-handed desk in the lecture hall and it made me so mad.

Madi: The other thing is can openers did you know this?

Curran: yeah everyone knows can openers.

Chromaphobe: All right, it’s unlikely that you’re convinced of their struggle, but it’s hard for them because like color blindness left-handedness is not really relatable. So let’s turn the stakes up a little bit.

Curran: All right I’m going to share a statistic with you: that left-handed industrial workers are about 5x more likely to suffer an amputation of a finger than a right-handed worker. So, imagine you’re working on a lathe or something… and just the fact that you have to operate it with your non-dominant hand or you have to contort yourself in a way where you can operate it with your left hand kind of puts you in a different position. It fatigues you faster. You make mistakes. All things that you probably wouldn’t attribute to your left-handedness.

Chromaphobe: And if I could decrease the risk of mutilation of my employees by 80% I feel like I’d be a shitty employer if I didn’t rearrange the lathe controls.

Madi: That’s crazy. I didn’t know that but when saying it, it makes sense… it makes sense that things are built for the majority of a general population. Makes total sense to me. I mean as an engineer developing devices to be used for medical professionals and even though [the tools] are largely ambidextrous, 90% of people are right-handed so we’re going to develop for the majority.

Curran: As someone who designs medical implements, how would you feel about having a left-handed surgeon versus a right-handed surgeon, knowing the left-handed surgeon is possibly going to have to use tools that were designed for a right-handed person?

Madi: Oh that’s tough. I mean… I would almost trust them more because they have to work extra hard to overcome that barrier so, um, it’s almost like… you know if they got that far then they’re guaranteed to be good.

Curran: Yeah, I saw another statistic: that doctors themselves are less happy to be operated on by a left-handed doctor because they know how handed those tools can be.

Madi: That’s insane. Yeah there’s certain… even imaging devices that are specifically “this goes in your right hand so that you use your left hand for something else” and vice versa. Yeah, okay, I’m going to actually correct what I said before. By default, if devices are made handed, you’re going to be at a disadvantage than the others.

Curran: Have you actually considered left-handedness to be a disability at any point?

Meghan: If disability is where you can’t do some things because of how you are then no. I can do everything the right-handed person can do so I would say no

Madi: I feel skeptical of saying disability because maybe it goes back to what you said earlier about making things trivial but I feel like you know others have it way worse there’s other disabilities that are way worse. So, you know, “oh I’m just left-handed it’s silly to say that I have a disability.”

Curran: Do you ever regret mom and dad not beating your left-handedness out of you?

Meghan: No, because I saw what happened to Grandpa and all of his issues and his stuttering and everything because it was beaten out of him.

Curran: Was that… is that what Dad attributes it to?

Meghan: yeah, Grandpa was left-handed and he was forced to use his right.

Curran: If that’s not showing it as a huge disadvantage… that literally being left-handed caused him a speech impediment, it seems like a pretty…

Meghan: No, what caused him a speech impediment was forcing him to be right-handed, not using his dominant hand…

Curran: …but in the society that is forcing him to do that it’s just an extra disadvantage put onto him.

Chromaphobe: At this point in the interview it seemed like a pretty good time to finally explain the different models of disability.

Curran: Okay, does that make sense?

Madi: Yeah, yeah, no, I’m on board. I understand. So, no, it wouldn’t fit into the the medical model but the society model that you explained… you’re right. Yeah, it’s, uh, there are certain barriers or certain elements in society that I would have to overcome to be equal to my counterparts, um, so being left-handed IS a disability.

Curran: …in the social model?

Madi: …in the social model.

Curran: Would you view through the social model that being left-handed is a disability?

Meghan: Yes, if you’re saying that it’s deemed as not the norm in society and therefore is harder to get along in society, then yes.

Curran: Do you think that society has some responsibility for accommodating left-handed people?

Madi: I do think so, especially in a professional sense (like the topics we were talking about earlier, you know in manufacturing or in medicine). It should not be that these professions or these activities are just, you know, not accessible to a percentage of the population because they’re left-handed… but to say that every pair of scissors I find there has to be a right-handed and a left-handed version next to it so that I’m accommodated, I would say that’s a level too far. Or, you know, just because there’s 10% of people that have a certain thing, do we have to make an effort to accommodate it, or whatever? Like, that’s probably the Devil’s Advocate side of this topic, is, you know, because I’m left-handed, um, does that mean everything needs to have a left-handed option?

Curran: You’re right that we can’t accommodate everyone and we can’t design things that are accessible to everyone. I can’t design a drill that’s accessible to someone who has no fingers. I don’t think anyone expects someone to design to the nth minority, and that’s why the left-handedness and the color blindness are so interesting because they are a large minority and so in most cases where you say “is it worth it to accommodate to those people?” I think the answer is always: YES. Even within color blindness you have certain kinds that are much more common than other kinds you look at red-green color blindness as way more prevalent than blue-yellow color blindness. So when I am explaining [to] people how to be more accessible to the color blind I tend to focus only on the red-green color blindness and it makes me feel bad every time I do that I kind of leave the blue-yellow color blind and the monochromats to the side and say, “well there’s not as many of them therefore they are not as… they’re not… it’s not as important to be accessible to them.” It is a numbers game. It is a numbers game, and if I was the only color blind person in the world I would not expect anything to be accessible to me but because I am one in 200 million colorblind people in the world, uh, my expectations go up. You need to pick the ones that are most impactful um which are the ones that are going to be the larger minorities…

Madi: the bigger market?

Curran: Yeah… the bigger market. Oh you say that…

Madi: It’s all capitalism man.

Curran: You say that and it sounds terrible… but yeah it is all capitalist, but, I mean, you still want to be as accessible to the most amount of people just from an equity point of view.

Meghan: …because it all just depends on the tools that we’re given and all the tools we’re given are made for right-handed people, but if all the tools were given were made for left-handed people, we’d be totally fine. If I lived in the woods and made my own tools for me, I would be just as capable as anybody else. So if society just like gives it up and changes just the teeniest tiniest bit, it’s not a disability anymore. So, yeah.

Conclusion

So c’mon society, just throw us a freakin’ bone. Really, just insignificant accommodations and lefthandedness could be 100% de-disabled and color blindness could be 90% de-disabled… enabled? That means that 90% of our disadvantages can be chocked up to restrictions imposed by society, mainly as career restrictions.

So have I convinced you that colorblindness is a disability…

Honestly, I don’t actually give a flying fart whether colorblindness surpasses some abstract threshold to gain entrance to the disability clubhouse, I don’t actually care if YOU think it’s a disability, but the frustrating thing is, in our society, if it’s not considered a disability, it’s not considered worthy of accommodation. I don’t need EnChroma lenses in scenic viewers in every national park, I just want police departments to be forced to spend an extra 50 bucks in buying a taser with a green laser instead of a red one for their colorblind cops.

I don’t even expect most of you to ever have to think about accommodating colorblind people. By all means, keep believing we all see in black and white and other nonsense, but if you are responsible for writing policy or employment regulations, god damn, I think the government needs to hold you accountable to being less of a dick to the colorblind.

This is Chromaphobe.

Leave a Reply